ADA elevator accessibility is the set of federal and state rules that determine how an elevator must operate so people with disabilities can use it safely and independently. In California, those requirements come from the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design, Title 24, and CBC 11B, along with enforcement from the Department of Justice. Together, they create strict expectations for how your elevator behaves every day.

Most compliance issues trace back to practical problems you’ve likely seen firsthand: call buttons mounted too high, doors that close too quickly, missing voice announcements, unreliable emergency communication, or car dimensions that don’t support wheelchairs or walkers. These barriers are also the source of many ADA demand letters and lawsuits. A qualified CASp inspection helps you catch these issues early and document the fixes that reduce liability.

This article explains the requirements for control panels, car size, voice and visual indicators, door timing, landing access, and the maintenance practices inspectors rely on when determining compliance.

What California Property Owners Should Know Up Front

California elevator accessibility rules come from both ADA standards and Title 24, which means inspectors look at how the elevator functions not just how it was originally built. Most violations involve predictable issues such as panel height, door timing, or communication failures, and none of these are protected by a grandfather clause. If an elevator serves the public, it must meet current accessibility requirements.

Here are the points that matter most:

California requires compliance with both ADA and Title 24. Title 24 often sets stricter criteria for controls, signals, and approach clearance, which is why California inspections catch issues owners weren’t expecting.

Control panel height is one of the most common violations. When buttons exceed the maximum reach range, users with mobility limitations cannot operate the elevator independently.

Door timing and sensor performance drive major accessibility failures. Doors that close too quickly or fail to detect users create immediate non-compliance.

Communication systems must function consistently. Missing voice announcements, unreadable visual indicators, or unreliable emergency phones are all accessibility barriers.

Older elevators are not exempt. Any alteration, modernization, or path-of-travel upgrade triggers current ADA and Title 24 requirements.

Accessibility issues create legal exposure. Many lawsuits start with simple problems like raised thresholds or malfunctioning communication features.

These fundamentals give you a clear picture of why California elevator compliance demands close attention and ongoing maintenance.

What ADA Elevator Compliance Means in California

ADA elevator compliance in California comes down to one idea: your elevator has to work in a way that people with disabilities can use it safely, predictably, and without assistance. The rules that define that standard don’t come from a single source. They’re a blend of federal and state requirements that work together and often overlap.

Here’s how the regulatory structure actually works:

2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design form the federal baseline. These rules define how elevator controls, door behavior, car dimensions, signage, and communication features must function for accessibility.

California Title 24 adds state-level requirements. Some measurements especially around controls, clearances, and signaling are more detailed or stricter than the ADA minimums.

CBC Chapter 11B reinforces how accessibility must be applied in California buildings. This is the section inspectors reference when they check layouts, reach ranges, and operational performance.

Local building departments review and permit elevator work, but DOJ handles enforcement. A malfunctioning or non-compliant elevator can trigger ADA complaints, investigations, and legal action, even if the local jurisdiction approved the installation.

These rules apply to commercial buildings, public accommodations, and shared areas of multifamily housing. In short, if the public or tenants rely on an elevator, it must meet both federal and California-specific accessibility requirements. Anything less counts as a barrier and exposes the owner to risk.

Misconceptions California Owners Commonly Have About ADA Elevators

Most accessibility problems start long before an inspection. They begin with assumptions owners pick up from contractors, outdated code summaries, or what the building “has always had.” These misunderstandings are so common that I see them repeatedly across retail buildings, offices, multifamily properties, and older mixed-use structures. Clearing them up early helps owners avoid expensive surprises once Title 24 and ADA rules are applied.

Here are the misconceptions that cause the most trouble:

- Old elevators are exempt.

They aren’t. The ADA has no grandfather clause, and California applies current requirements whenever the elevator serves the public or shared areas. Alterations, modernization, and path-of-travel upgrades all trigger compliance. - If the elevator passed its state safety test, it must be ADA compliant.

A safety inspection under ASME A17.1 evaluates mechanical and operational safety, not accessibility. An elevator can pass its annual safety test and still fail CASp or DOJ accessibility review. - My building is small, so voice announcements aren’t required.

Floor announcements, door signals, and visual indicators apply to any public-serving elevator, regardless of building size. - Only the interior car matters for ADA.”

In reality, inspectors evaluate the entire route. A compliant cab does not offset an inaccessible landing, tight corridor, or sloped approach. - Modernization doesn’t trigger ADA or Title 24.”

It does. Any work that changes controls, doors, communication systems, or interior layouts brings the elevator under current requirements.

These misconceptions lead to the most avoidable violations. When owners understand how ADA and Title 24 actually apply, they can plan upgrades with fewer surprises and address risks before they escalate.

What ADA Covers vs What ASME A17.1 Covers

Most owners mix these two systems together. That’s where mistakes start. ADA accessibility rules and ASME A17.1 safety codes do not do the same job, and treating them as one set of requirements leads to violations during modernization and TI work.

Here’s the clean separation.

What ADA + Title 24 Cover (Accessibility Rules)

These rules focus on how a person with a disability uses the elevator:

Reach ranges for all interior and hall controls

Door timing and reopening sensors

Clear floor space, turning radius, and usable interior layout

Audible floor announcements and visual indicators

Emergency communication usable without speech or hearing

Path of travel to the elevator, including slopes, landings, and clearances

These are usability standards. The elevator might run fine mechanically, but if someone can’t reach the controls or the doors close too fast, it fails ADA and Title 24.

What ASME A17.1 Covers (Safety and Mechanical Rules)

These rules focus on how the elevator operates mechanically:

Brakes

Leveling accuracy

Hoistway conditions

Fire service operation

Emergency power

Door protection under mechanical requirements

Car top access

Structural and electrical safety systems

None of these set accessibility measurements. A car can pass every A17.1 test and still be unusable for a wheelchair user. I see this often when modernization focuses on hardware but skips reach ranges or door timing.

The Practical Takeaway

ADA + Title 24 = usability for people with disabilities

ASME A17.1 = mechanical safety

Passing one does not mean you pass the other

California enforces both, independently

This is where owners get caught off guard. The elevator “works,” but still violates accessibility rules because the usability features weren’t updated.

When “Maintenance” Becomes an ADA-Triggered Alteration in California

Most owners assume elevator service work is “just maintenance.” Often, it isn’t. When a repair changes how a user reaches, operates, or moves within the elevator, California treats it as an ADA-triggering alteration under Title 24 and CBC 11B. I see this mistake more than almost any other.

Here’s the practical break-down.

What Counts as Routine Maintenance (No ADA Trigger)

These tasks keep the elevator safe and functional, but do not change accessibility features:

Mechanical repairs

Motor work, sheaves, controllers, brakes, pumps, relays.Leveling adjustments

Routine leveling checks that don’t change thresholds or landings.Cleaning and lubrication

Standard service stops.Replacing like-for-like parts

Lamps, hinges, identical fixtures, matching hardware.

Routine work doesn’t require ADA upgrades. You are restoring the elevator, not altering how a person uses it.

What Counts as an Alteration (ADA + Title 24 Trigger)

When a repair changes the way a user interacts with the elevator, it becomes an alteration under accessibility law.

Here are the situations that trigger compliance:

Control panel replacement

New buttons or new panel location → must meet ADA reach ranges and Title 24 contrast rules.Door operator replacement

New door equipment → must meet dwell time, reopening response, and sensor standards.Cab interior remodel

Panels, handrails, finishes → can reduce usable floor space or turning radius.Flooring replacement

Thicker flooring raises thresholds. I see this fail often.Call station relocation

If the landing button moves, the height must meet ADA/T24 limits.

Once an alteration happens, inspectors evaluate all related elements that affect usability. Not just the replaced part.

The Legal Line California Uses

California uses a simple rule:

If the work affects how a person with a disability reaches, enters, operates, or exits the elevator, ADA and Title 24 apply.

This rule is strict because most lawsuits come from small, overlooked alterations that created barriers unintentionally.

Why This Matters for Owners

Here’s the real-world impact:

Many “repairs” unintentionally create ADA violations.

Subcontractors rarely consider reach ranges or turning space when replacing parts.

Insurance disputes often cite non-compliant alterations.

A modernization done without accessibility review becomes a long-term liability.

In reality, a single alteration can turn a previously usable elevator into a barrier overnight.

Common ADA Elevator Failures in California Buildings

Most ADA elevator problems in California are not surprises. Inspectors, tenants, and even Reddit users describe the same patterns: people can’t reach the controls, doors move too fast, or the elevator is technically “working” but still unusable for someone with a disability. If you own or manage a building, these are the failures that quietly create the most risk.

Control panels mounted too high. When the highest elevator controls sit above the allowed reach range, a wheelchair user or someone with limited shoulder movement cannot use the elevator independently. This is one of the most common findings in older or “modernized” cars that never had control heights corrected.

Buttons without proper tactile and Braille markings. Floor and control buttons must have tactile characters and Braille in specific locations and sizes. Missing, tiny, or misplaced markings mean blind and low-vision users can’t navigate floors safely, even if the elevator otherwise runs fine.

Door timing that rushes users. Elevator doors must stay open long enough for someone with a mobility aid to enter and exit without rushing. When doors close quickly or sensors miss someone in the opening, users feel unsafe and inspectors flag it as a barrier.

Missing or inconsistent audible and visual signals. Chimes, floor announcements, and indicator lights are part of the accessibility system, not “nice extras.” When they’re broken, turned off, or only work intermittently, people who rely on sound or visual cues lose essential information.

Inaccessible route to the elevator. A compliant car doesn’t fix a bad approach. Steep slopes, raised lips at thresholds, narrow corridors, or clutter in front of elevator doors can all turn the path of travel into a violation, even when the elevator itself meets code.

Emergency communication that doesn’t serve all users. Emergency phones and two-way communication must work for people who can’t see, hear, or speak clearly. Broken call buttons, unclear instructions, or systems that don’t connect reliably are frequent inspection failures.

Elevator cars that are too small for mobility devices. Cars that don’t provide enough space for a wheelchair to enter, turn, and position safely are treated as barriers. This shows up often in older buildings where cab size was never upgraded to current accessibility dimensions.

If you recognize more than one of these issues in your building, you’re not alone. These are exactly the kinds

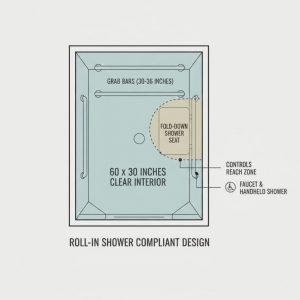

ADA and Title 24 Requirements for Elevator Size, Car Layout, and Turning Space

Elevator size and interior layout determine whether a person using a wheelchair or mobility device can enter, turn, and ride safely. California uses the ADA Standards, along with Title 24 and CBC 11B, to set these measurements. Inspectors focus on these dimensions because many older elevators simply don’t provide the maneuvering space required today.

Before diving into the specifics, here’s what shapes the size and layout requirements:

ADA establishes the baseline dimensions. These measurements define how much clear space is needed for safe entry, turning, and positioning.

Title 24 adds California-specific adjustments. These rules refine clearances, door widths, and usable interior space.

CBC 11B ties the requirements to actual building conditions. Inspectors use this section when checking how interior features affect mobility.

Together, these standards create the size expectations every California elevator must meet if it serves the public.

What size does an ADA elevator need?

Most owners want a straightforward answer here, and there is one: Yes, the ADA sets minimum interior sizes for accessible elevators, and California applies these measurements through both ADA Standards and Title 24. The numbers matter because even small deviations can block a wheelchair user from entering or turning.

The most common requirements include:

Approximately 51 by 80 inches of clear floor area. This configuration supports forward and side entry for many mobility devices. Some layouts require different dimensions, but this is the layout typically seen in compliant commercial elevators.

A minimum of 36 inches of clear door width. A door that is too narrow makes the interior space irrelevant, because a mobility device cannot enter in the first place.

Additional width or depth in some Title 24 jurisdictions. Inspectors sometimes require slightly larger clearances to account for handrails, control panels, or wall projections that reduce the usable space.

If the car is too small or the doorway is too tight, the elevator is treated as non-compliant regardless of its age or mechanical condition.

Required Turning Space, Handrails, and Floor Clearances

Turning inside the cab is part of independent use, which is why inspectors check how much usable space remains once a wheelchair enters. The ADA requires room for a 180-degree turn, and Title 24 reinforces that requirement by evaluating how features inside the cab affect movement.

Here’s what typically comes under review:

Turning space inside the cab. The user must be able to rotate without contacting walls or fixtures. Control panels, rails, or deep returns can shrink the turning circle more than owners expect.

Clear floor space at the entry. The first few feet inside the door must allow the user to move out of the opening without hitting a threshold or corner.

Handrail height and projection. Handrails are permitted but must stay within limits so they don’t reduce the usable interior. Oversized or protruding rails are a common source of violations.

When any part of the interior layout restricts movement, the elevator no longer supports independent use, and California treats it as an accessibility failure under both ADA and Title 24.

ADA Elevator Door Requirements: Width, Speed, and Timing

Elevator doors create many of the day-to-day access problems that users report. A car can meet interior size rules, but if the doors move too quickly or the opening is too narrow, people using mobility devices simply cannot enter. California inspectors pay close attention to this area because most complaints come from door behavior, not the mechanics of the car itself.

Door Width Standards for ADA and Title 24

Yes. Elevators must provide a minimum of 36 inches of clear door width under the ADA, and California applies this same threshold through Title 24. This measurement refers to the actual clear opening when the doors are fully open, not the nominal size listed by the manufacturer.

Some California buildings require slightly more usable width when interior handrails or deep returns reduce maneuvering space inside the cab. Inspectors also look at how the door interacts with the landing. A compliant opening is not enough if a raised threshold or tight corner forces a mobility device to angle in.

If the clear width falls below the required measurement, the elevator is treated as a barrier because the user cannot enter safely or independently.

Door Timing and Reopening Requirements

Yes. Elevators must follow specific timing, sensor, and reopening rules to ensure users have enough time to enter and exit safely. Most violations in California involve doors that close too quickly or sensors that fail to detect someone standing in the opening.

Here are the key elements inspectors typically verify:

Dwell time. The doors must stay open long enough for a person using a wheelchair, walker, or cane to move through the opening without rushing. Short dwell times are a common source of user complaints.

Reopening sensors. Elevators must detect a person or mobility device in the path of the closing doors. If the sensors miss someone in front of the door, the elevator is treated as non-compliant because it creates an immediate safety and accessibility issue.

Obstruction behavior. When the door meets resistance, it must reopen promptly and not continue pressing against the user. Improper obstruction response is a frequent finding during inspections, especially in older elevators that have not had their sensors updated.

Together, these standards determine whether the doors support independent use. California treats timing and sensor failures seriously because they affect real-world safety, not just technical compliance.

Elevator Control Panel Requirements: Height, Reach Range, and Tactile Features

Control panels are one of the most common trouble spots in California inspections. When the buttons are too high, too small, poorly marked, or missing tactile features, people cannot operate the elevator independently. Title 24 and the ADA both set clear rules for height, reach range, and how buttons must be labeled. Inspectors look at these details closely because they affect everyday usability, not just technical compliance.

ADA-Compliant Control Panel Height in California

Yes. Elevator controls must fall within specific reach ranges, and California enforces these limits using both ADA Standards and Title 24. The question most owners ask is simple: “How high can the buttons be?” The answer depends on whether anything blocks the user from reaching them.

Here are the key height rules:

48 inches maximum when the user can reach the controls directly. This is the standard ADA reach range for an unobstructed forward or side approach.

44 inches maximum when the reach is obstructed. If the user has to reach over a handrail, return panel, or other fixed obstruction, the controls need to be lower.

Hall call button height is measured separately. These buttons follow similar reach rules but are evaluated at the landing rather than inside the cab.

If any control is placed above the allowed reach range, the elevator is considered non-compliant because a wheelchair user cannot operate it without assistance.

Button Size, Spacing, and Tactile/Braille Requirements

Controls must be easy to find, easy to read, and easy to press. Inspectors review each button to confirm the markings and tactile features meet California and ADA standards.

These are the requirements most often checked:

Raised characters that you can feel. Letters or numbers must be raised enough for a blind or low-vision user to identify them by touch.

High visual contrast. Characters must contrast clearly with the background. Title 24 emphasizes this because low-contrast buttons are difficult to identify under low light.

Illuminated indicators. Buttons must light up when pressed so users know the command was received.

Correct Braille placement. Braille must appear directly below the raised characters and be sized and spaced according to ADA and Title 24 rules.

When these features are missing or inconsistent, the controls become an accessibility barrier even if the elevator’s mechanics work perfectly.

Audible Voice Announcements and Visual Indicators

Independent use depends on more than buttons. People who cannot see or hear well rely on the elevator’s communication system to navigate floors safely. Both ADA Standards and Title 24 require consistent audible and visual indicators.

Inspectors verify three elements:

Floor announcements. A verbal announcement must identify each floor as the elevator arrives. This helps blind or low-vision users know where they are.

Door opening and closing signals. Audible tones and visual indicators must signal when doors are opening or closing. When these fail, users cannot time their movement safely.

Emergency communication that serves all users. The emergency phone or two-way system must work for people who cannot hear, speak, or see clearly. Systems that require verbal speech only are treated as barriers.

When these communication features are unreliable or missing, the elevator cannot be considered accessible under California or federal rules.

Emergency Communication and Safety Features Required in ADA Elevators

Emergency features are not optional. They allow people who cannot see, hear, or speak clearly to understand where the elevator is and call for help.

- Accessible emergency communication is required under ADA Standards and Title 24, and inspectors check these features closely because failures affect real safety, not just technical compliance.

- These are the features reviewed during accessibility testing:

- Audible floor announcements

The elevator must speak each floor as the car arrives. Blind or low-vision users rely on this to orient themselves. - Visual indicators

Displays must show direction and floor position. They must be bright and readable from inside the cab and at the landing. - Door movement signals

A clear tone or light must indicate when doors begin to open or close. Weak tones and dim indicators are common reasons elevators fail Title 24 checks. - Emergency communication system

Users must be able to call for help even if they cannot see, hear, or speak. Systems that rely on spoken communication only do not meet accessibility requirements. - Instruction placement

Emergency instructions must be mounted where users can reach and read them. Title 24 checks character size, contrast, and placement. - An elevator cannot be considered accessible if any part of the emergency communication system is unreliable. These features protect people during the moments when they need clarity the most.

Path of Travel Requirements Leading to Elevators in California

Access to an elevator starts long before someone reaches the doors. California treats the path of travel as part of the elevator system itself because a user cannot rely on the car if they cannot reach it safely. Inspectors focus on slopes, clearances, landings, and signage, and these areas often create violations even when the elevator is fully compliant. If the approach route is narrow, steep, or poorly marked, it becomes an accessibility barrier under both ADA Standards and California Title 24.

Does ADA apply to the path leading to an elevator?

Yes. The ADA and Title 24 both require an accessible path of travel to the elevator, and California treats path issues as direct accessibility failures. This includes ramps, corridors, landings, thresholds, and any transition from the surrounding floor area into the elevator lobby. A compliant elevator does not offset a non-compliant route.

Here are the key elements inspectors review:

Slope limits. The approach route must stay within allowable slope ranges for accessible routes. If the slope exceeds the limit or the cross-slope forces a mobility device to drift, the path is considered unsafe.

Landing requirements. Landings at the elevator call station must provide level, stable space for a wheelchair user to wait without blocking circulation. Uneven surfaces, sloped pads, or small waiting areas are common failures.

Doorway clearances. The space in front of the elevator doors must allow users to turn, position, and approach directly. Tight corners, raised thresholds, or door swings from adjacent rooms often reduce this space.

Signage when the elevator is out of service. If the elevator is down, accessible signage must direct users to an alternate accessible route. California requires clear, readable signs that a low-vision user can identify easily.

California-specific access aisle considerations. Some elevator lobbies require wider access aisles to accommodate turning and waiting space, especially in multifamily or public buildings where multiple users may queue at once.

When any part of the path of travel is too steep, too narrow, or poorly marked, the elevator is considered functionally inaccessible even if the car meets every technical requirement.

California Title 24 Requirements That Are Stricter Than Federal ADA

California does not simply mirror the ADA. Title 24 and CBC 11B add their own performance rules that tighten how elevators must operate and how users interact with controls, signals, and communication systems.

Here are the areas where California is stricter than the ADA:

Tactile sign requirements. Title 24 lays out detailed rules for character size, thickness, and letterform that exceed the ADA’s minimums. Inspectors check the height, shape, and placement of tactile characters around elevator controls and landings more closely than federal standards require.

Button illumination rules. California expects consistent illumination that is bright enough for low-vision users to see clearly. ADA requires illumination but Title 24 is more exact about contrast and visibility, especially in dimly lit elevator lobbies.

Control panel contrast. Title 24 places a stronger emphasis on visual contrast between buttons, characters, and background surfaces. Panels with low-contrast finishes that technically meet ADA often fail in California because users cannot distinguish controls quickly.

Audible signal thresholds. ADA requires audible cues, but Title 24 further defines how loud, clear, and consistent those tones must be. Weak chimes or muffled announcements that pass under ADA often do not meet California’s expectations.

Emergency phone standards. California enforces communication rules that support users who cannot hear, speak, or see clearly. The emergency system must provide equivalent access for all users, which is a higher bar than ADA’s baseline requirement for two-way communication.

Path of travel reinforcement. Title 24 strengthens how approach routes, landings, and clearances are evaluated. A path that might pass under ADA can be considered non-compliant in California if turning space, slope, threshold height, or waiting area conditions reduce independent access.

These differences matter because inspectors treat Title 24 as the enforceable standard in California. An elevator that meets ADA alone is not considered compliant if it falls short of state-level requirements.

How Local California Jurisdictions Enforce Elevator Accessibility

ADA and Title 24 rules apply statewide, but enforcement is handled locally. Some jurisdictions review elevator accessibility with more scrutiny. I see this during plan checks and final inspections when different counties expect different levels of detail.

Here is how enforcement usually varies:

- Los Angeles

Plan check reviewers in LA commonly request more detail on control panel contrast, signage placement, and landing clearances. They tend to ask for clarifications that other jurisdictions accept without revision. - San Francisco

San Francisco focuses heavily on path of travel, lobby turning space, and landing conditions. Older buildings often face extra review because interior constraints limit layout options. - San Diego and Orange County

These regions emphasize operational consistency. Inspectors spend more time on door timing, signal clarity, emergency communication, and sensor response. - Local amendments and administrative practices

Some cities require additional documentation for door operators, modernization projects, or communication systems. Others want pre-testing before the inspection is scheduled. - The rules do not change across the state, but how closely they are examined does. That difference affects permitting, timelines, and the depth of required corrections.

ADA vs ASME A17.1 Safety Code: Clearing Up the Confusion

A lot of owners assume that if the elevator passes its annual state safety inspection, it must also meet ADA and Title 24. I see this confusion almost every week. The problem is that safety and accessibility are two separate evaluations, and they measure very different things.

- ASME A17.1 is a safety code.

It looks at brakes, cables, emergency operations, door pressure, and mechanical systems. It makes sure the elevator is safe to ride. - ADA and Title 24 are accessibility standards.

They look at reach ranges, door timing, interior dimensions, audible cues, visual indicators, and communication access. They make sure people with disabilities can use the elevator independently.

Here’s the practical side:

- A17.1 does not measure accessibility.

An elevator can pass every safety test and still fail ADA and Title 24 because the controls are too high, the doors close too quickly, or the communication system doesn’t serve all users. - ADA and Title 24 do not measure mechanical safety.

They focus only on whether the elevator can be reached, entered, operated, and exited by people with disabilities. - I see owners rely on safety certificates as proof of compliance. It happens often in older properties. The truth is that a current safety tag tells you nothing about accessibility. If the elevator serves the public or common areas, both systems must be met at the same time:

A17.1 keeps the elevator safe. ADA and Title 24 make it usable.

What Happens After You Fail an Elevator Accessibility Inspection

Most owners expect a simple correction list when an elevator fails an accessibility review. In California, the process is more structured. Once ADA or Title 24 violations are confirmed, the owner becomes responsible for removing the barriers and documenting corrective actions. I see the same sequence repeat in retail centers, office towers, and multifamily buildings. Knowing what comes next helps you plan the work before it escalates.

What does the inspector do after identifying violations?

The inspector documents the barrier and notes which ADA or Title 24 rule it violates.

That documentation becomes the basis for corrective work. The findings usually include measurements, photos, and a description of how the issue affects independent use. For example, if a control panel is mounted above the reach range, the report will reference the specific ADA and Title 24 height limits.

Will the building receive a notice or written report?

Yes. A written report is issued, and it becomes part of the project record.

For CASp inspections, this report outlines barriers and ranks them by priority. For building department inspections tied to permitted work, the findings may be listed as corrections that must be resolved before final sign-off. In both cases, the report shows what has to be fixed and why.

How much time do owners have to correct the issues?

Correction timelines depend on the type of inspection and the severity of the barrier.

If the issue is tied to a permit, it must be resolved before the project can close. CASp findings are handled differently. The owner receives a window of time to remove barriers, and the CASp program recognizes documented good-faith effort. In practice, owners move more quickly because unresolved barriers can lead to complaints.

What are the next steps after receiving the findings?

Owners must review the violations, obtain proposals from qualified elevator contractors, and plan the corrective work.

Most accessibility issues involve reach ranges, door behavior, signal systems, or path-of-travel barriers. Mechanical safety work is performed by licensed elevator contractors, and accessibility features must meet both ADA and Title 24 requirements. The documentation from the inspector guides what needs to be corrected.

How does this escalate if the issues are ignored?

Unresolved barriers can lead to complaints, demand letters, or DOJ involvement.

I’ve seen cases where a single issue, such as missing voice announcements, triggered a formal complaint after months of inaction. California treats elevator accessibility failures as violations affecting daily use, not optional upgrades. Leaving them unresolved exposes the building to legal and financial risk.

Does a CASp inspection help during this process?

Yes. A current CASp report offers legal protections and helps owners prioritize the work.

It documents barriers, shows intent to comply, and gives owners a structured way to manage corrections. This often reduces exposure if a claim is filed. CASp inspections also help owners understand which corrections are required immediately and which can be planned across multiple phases.

The process is manageable when you understand each step. The sooner barriers are identified and corrected, the easier it is to avoid complaints, delays, and unexpected costs.

When an Elevator Becomes “Non-Compliant” Under ADA or Title 24

Property owners often assume older elevators are exempt from accessibility rules. They are not. The ADA has no grandfather clause, and California treats non-compliant elevator features as barriers whenever they affect public use. I see this misunderstanding often during inspections. A building may be decades old, but once certain work is done, the elevator must meet current ADA and Title 24 requirements.

Here are the situations that trigger full compliance:

Alterations. Any work that affects the elevator’s function or usability brings the system under current rules. This includes changes to controls, interior finishes, doors, or communication features.

Modernization projects. When a building updates mechanical systems, cabs, doors, or control equipment, inspectors evaluate the renovated elements against today’s standards. Modernization is one of the most common triggers in California.

Tenant Improvements. TI work that impacts the path of travel, lobby layout, or access to building services brings the elevator into review. If people must reach the elevator to use the space, the system must comply with current standards.

Path of travel upgrades. When ramps, corridors, entries, or common areas are updated, the elevator becomes part of the accessible route and must meet current ADA and Title 24 requirements.

Change of use. When a building or floor changes occupancy type, the accessibility requirements shift. An elevator that was acceptable under the previous use may no longer meet the needs of the new occupancy.

In reality, an elevator becomes non-compliant the moment its features create a barrier for someone who relies on accessible use. California treats these triggers seriously because most accessibility issues show up in buildings that were never updated after alterations or modernization.

Costs of ADA Elevator Upgrades and Modifications in California

Owners usually ask the same question when a CASp report calls out elevator issues: how much will it cost to fix this? The answer depends on what the elevator is missing and whether the building can support the required upgrades. California projects tend to cost more than national averages because Title 24 demands tighter performance, and most work requires permits, inspections, and licensed elevator contractors. I’ll keep the ranges factual and grounded in what California projects typically show.

Here is how the main cost categories break down:

Control panel relocation. Repositioning controls to meet reach ranges usually falls between fifteen and forty thousand dollars depending on wiring routes, panel size, and cab configuration. Costs rise when the panel needs reconstruction rather than surface adjustments.

Door automation and sensor upgrades. Updating door operators, adding compliant sensors, or correcting dwell timing often ranges from eight to twenty-five thousand dollars. Older doors with worn mechanical systems land at the higher end because more components need replacement.

Signals and communication systems. Bringing audible announcements, visual indicators, and emergency communication into compliance typically runs from five to twenty thousand dollars. Buildings with outdated emergency phones or unreliable annunciators may need full system replacement.

Car enlargement. Expanding an elevator car to meet current ADA and Title 24 dimensions is the most variable cost because it depends on the hoistway structure. Some buildings cannot enlarge the cab without major structural work. When enlargement is possible, projects often start around one hundred thousand dollars and can exceed three hundred thousand in tight shafts.

Partial upgrades versus full modernization. Limited upgrades address specific violations, but full modernization replaces major components such as controls, doors, communication systems, and interior finishes. Modernization projects in California frequently range from one hundred and fifty thousand to five hundred thousand dollars depending on building size and equipment type.

Permitting and inspections add additional cost. Most counties require elevator work to be reviewed by building departments, and the final inspection is completed by a state-licensed elevator inspector. Permit fees and inspections usually range from a few hundred dollars for minor work to several thousand for large modernization projects.

Costs vary, but the pattern is consistent. Smaller accessibility fixes remain manageable, while structural limitations and older equipment push projects into higher ranges.

Required Documentation for Elevator Accessibility Compliance

Owners often overlook paperwork until a complaint or inspection forces the issue. Accessibility documentation is the record that shows whether you maintained the elevator, tested key features, and followed ADA and Title 24 requirements. When documentation is weak or missing, owners lose footing in both CASp reviews and legal disputes.

Here are the documents that matter most:

Service and maintenance logs

These show when technicians tested door timing, sensors, communication systems, and illumination. I see many buildings that service the mechanics but never document accessibility features.

Modernization and alteration records

Any upgrade that affects controls, doors, or communication systems becomes subject to current ADA and Title 24 rules. Inspectors review dates and scope to confirm whether those changes triggered compliance requirements.

Accessibility testing reports

Clear reports on dwell timing, reopening response, button illumination, Braille placement, and audible signals. Missing test history weakens your position during enforcement.

Emergency communication certifications

Records showing the phone or two-way system provides equivalent access for users who cannot speak or hear. Systems fail accessibility audits when owners cannot prove this.

CASp inspection reports

A current CASp report documents barriers, timelines, and your intent to comply. When claims arise, this report often carries more weight than anything else.

Good documentation will not fix violations, but it shows you acted in good faith and followed a structured compliance process.

Legal and Financial Risks of Non-Compliant Elevators in California

When an elevator doesn’t meet ADA or Title 24 requirements, the risk goes far beyond an inspection note. In California, accessibility failures often turn into legal action, insurance disputes, or costly tenant conflicts. I see owners underestimate this all the time, especially when the elevator “seems to work” but still creates barriers for people with disabilities. The law looks at usability, not convenience, and the consequences fall directly on the property owner.

Here are the main risks you should be aware of:

Department of Justice enforcement. The DOJ investigates elevator barriers when they affect public access. Even a single complaint from a tenant or customer can trigger a review.

Civil penalties. Federal ADA violations can lead to penalties that increase if the barrier affects multiple users or has been ignored for a long period.

Daily fines for continued non-compliance. Once a violation is confirmed, owners can face accumulating fines until the barrier is corrected. California takes this seriously when elevators serve essential access routes.

Demand letters. Many ADA cases in California start with private demand letters. These often cite reach range issues, door timing problems, or failed communication systems.

Injury liability. If someone is injured because of door behavior, sensor failures, or inaccessible panels, the owner may face claims that combine ADA violations with personal injury allegations.

Tenant complaints. Multifamily buildings see frequent elevator complaints on Reddit and similar forums. Tenants describe being unable to reach buttons, missing floor announcements, or getting stuck due to timing issues. These complaints often escalate to formal accessibility claims.

Insurance complications. Some insurers raise questions or deny parts of a claim when the elevator was operating out of compliance at the time of an incident. Non-compliant equipment makes coverage disputes more likely.

These risks compound quickly. In California, a non-compliant elevator isn’t viewed as a maintenance issue. It is treated as a barrier under the ADA and Title 24, which puts real financial and legal pressure on the property owner until the issue is resolved.

How CASp Inspections Reduce Elevator-Related Liability

What a CASp Inspector Checks in Elevators

Yes. CASp inspectors evaluate elevators against ADA Standards and California Title 24, and the review covers more than just the elevator cab. The goal is to confirm that a person with a disability can reach, enter, operate, and exit the elevator safely and independently.

Here are the areas typically reviewed:

Measurements. Inspectors verify interior dimensions, door widths, control panel heights, and reach ranges. Small deviations often create the biggest barriers.

Timing tests. Door dwell time, reopening response, and sensor performance are tested to see whether users have enough time to move safely.

Signal compliance. Audible announcements, visual indicators, and button illumination are checked for clarity and consistency.

Path of travel review. Inspectors examine the approach route, landing, slope conditions, and waiting area to confirm the elevator is reachable without barriers.

Documentation audit. Maintenance records, modernization history, and service reports help determine whether the elevator has unresolved issues that affect accessibility.

A thorough inspection often reveals problems that daily riders have been dealing with long before they were documented.

Benefits for Building Owners (Qualified Defendant Protections)

A CASp report does more than list violations. It gives owners a structured way to manage risk and plan barrier removal. When done early, it also qualifies the owner for legal protections under California law.

Here are the main advantages:

Early identification. Owners learn about reach range issues, faulty sensors, or communication failures before they turn into complaints or claims.

Prioritized barrier removal. CASp reports rank issues so owners know which elevator barriers need attention first based on safety and accessibility impact.

Reduced legal exposure. Buildings with a current CASp inspection often resolve claims faster because they can show documented intent to comply with accessibility rules.

Notice and cure period. California provides additional time to address barriers when a CASp report is in place. This protection is valuable when dealing with complex elevator modifications.

CASp inspections are especially useful in properties that serve the public or multifamily residents. When needed, you can also seek ADA-focused evaluation for multifamily buildings through services which helps owners address elevator access issues as part of a broader accessibility plan.

Responsibilities When an Elevator Is Temporarily Out of Service

- When an elevator stops working, access stops with it. Accessible route continuity is required under ADA Standards and Title 24. A temporary outage does not remove that obligation. The problem is not only the mechanical failure. It is the lack of a safe, accessible route for users who rely on the elevator.

- Owners are expected to handle four things immediately:

- Accessible signage

Clear signs must be posted at entrances and elevator lobbies. They must direct users to another accessible route or state that no accessible route exists. Signs must follow visibility and character rules. - Alternate accessible route

If another elevator or lift is available, users must be directed to it. If the building has no alternate route, the outage becomes a compliance concern until repaired. - Timely repair

Long delays increase exposure. A prolonged outage is treated as a barrier under ADA and Title 24. - Communication with residents and visitors

Notices help people plan, but they do not remove legal responsibility. Multifamily buildings see the most complaints when outages are not managed correctly. When the elevator is down, the building must still offer a reliable way for people to reach the floors they need. If no alternative exists, quick repair becomes the only compliant path.

California ADA Elevator Compliance Checklist (Step-by-Step)

A compliance checklist helps owners move through elevator issues in a clear, orderly way. The goal is to verify the features that affect daily use: reach ranges, door behavior, signals, communication, and the path of travel. When these areas are checked in sequence, you get a realistic picture of where the elevator stands under ADA and Title 24. This approach works well for owners who want to prevent complaints and reduce liability before problems escalate.

Here are the steps to follow:

Measure all control panel heights. Confirm that interior controls and hall call buttons fall within the required reach ranges. Small variations often create the most significant barriers for wheelchair users.

Test tactile characters and Braille. Each button should have raised characters with correctly placed Braille that is easy to read by touch. Inconsistent placement or low contrast is a common failure point.

Verify door timing. Check how long the doors stay open and how the sensors respond when someone is in the opening. If doors close too quickly or fail to detect movement, the elevator is treated as non-compliant.

Check the communication system. Test the emergency phone, visual indicators, floor announcements, and any two-way communication features. Systems that rely on speech or hearing only are not accessible for all users.

Confirm car size and turning radius. Measure the interior space to ensure a wheelchair can enter, turn, and position without contacting walls or fixtures. Door width must also meet the required clear opening.

Inspect the path of travel. Review slopes, landings, thresholds, and waiting areas leading to the elevator. A compliant car does not offset an inaccessible approach route.

Review maintenance logs. Look for repeated issues such as sensor failures, door behavior problems, or inconsistent signals. These patterns can point to underlying accessibility concerns.

Schedule a CASp inspection. A CASp review provides a verified assessment of ADA and Title 24 compliance and helps owners prioritize barrier removal based on risk.

Document fixes and re-test. After repairs or adjustments, confirm that all features work consistently. Proper documentation supports compliance efforts and reduces exposure in case of a future claim.

Working through this checklist creates a structured way to evaluate elevator accessibility and prepare for a more complete assessment. Whenever needed, owners can also seek subtle accessibility guidance for retail properties or similar support through qualified consultants to ensure their elevators remain usable and compliant over time.

Common Questions About ADA Elevator Requirements in California

Are old elevators exempt from ADA rules in California?

No. Older elevators are not exempt from ADA requirements, and California does not provide a grandfather clause. When an elevator serves the public or a common area, it must comply with current ADA Standards and Title 24. Any alteration, modernization, or path of travel upgrade triggers full compliance. In practice, many violations come from older cars that were never updated after building changes, even though tenants still rely on them every day.

Can a lift replace an ADA-compliant elevator in a commercial building?

No. A platform lift cannot replace an ADA-compliant elevator in most commercial buildings. The ADA allows lifts only in limited situations, such as small occupancy loads or specific alterations where an elevator is not technically feasible. Title 24 is even stricter. For multistory commercial buildings, an elevator is the required method of vertical access. Lifts are not a substitute when the building is expected to serve the general public.

What if my elevator is too small to meet ADA size requirements?

Yes and no. An undersized elevator can remain in use, but it is still considered non-compliant when it cannot meet ADA and Title 24 dimensions. If the car is too small for a wheelchair to enter and turn safely, it becomes an accessibility barrier. Some buildings can expand the hoist way, but many cannot without structural work. When enlargement is not possible, owners typically address all other barriers and document the structural limitations during a CASp inspection to manage risk.

Does ADA require voice announcements in all elevators?

Yes. Elevators serving the public must provide audible floor announcements and visual indicators. These features help blind, low-vision, and deaf users understand movement and destination. Title 24 also reviews clarity, consistency, and volume thresholds. If the announcements are faint, distorted, or missing, inspectors treat the system as non-compliant even if the elevator otherwise operates normally.

How often must elevator accessibility features be tested?

Yes. Elevator accessibility features must be tested regularly as part of ongoing maintenance. Door timing, button illumination, audible signals, visual indicators, and communication systems must function consistently. Many California owners review these features during scheduled servicing because accessibility failures often show up before major mechanical problems. Regular testing also supports compliance documentation, especially in multifamily and public-serving buildings.

Final Considerations for California Elevator Compliance

Elevator accessibility is more than a code requirement. It affects safety, daily usability, and the level of legal risk a building carries. When doors close too quickly, controls are out of reach, or announcements fail, people feel the impact immediately. In California, these issues also carry financial consequences because ADA and Title 24 treat each barrier as a compliance failure.

A focused approach makes the process manageable. When owners measure reach ranges, check door timing, review communication systems, and confirm turning space early, they avoid the costly repairs and claims that come from long-ignored problems. This is where a CASp inspection brings real value. It identifies barriers before they escalate, prioritizes what to fix first, and documents your efforts to comply. That combination reduces liability and helps owners plan upgrades without surprises.

If your building relies on an elevator to serve tenants or the public, early evaluation is the simplest way to keep people safe and protect the property from avoidable claims.

Trusted Legal Standards and Compliance Resources

2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design

U.S. Department of Justice – official ADA standards for elevator dimensions, controls, communication systems, and accessible routes.

https://www.ada.gov/law-and-regs/design-standards/

ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) – Elevator Requirements

https://www.access-board.gov/ada/guides/chapter-4-elevators-and-platform-lifts/

California Building Code (CBC) Chapter 11B – Accessibility to Public Buildings

California Title 24 Accessibility Regulations